- Home

- Ashley McConnell

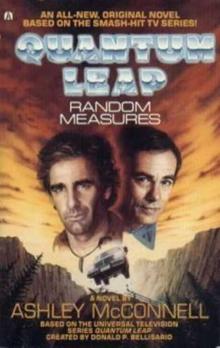

Quantum Leap - Random Measures

Quantum Leap - Random Measures Read online

AND WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN ALL MY LIFE?

"Albert.” Unlike certain previous wives—Al wondered suddenly how many previous wives he’d had in this particular timeline—her use of his name indicated great patience and a certain amount of humor.

He closed his eyes and shook his head. “It’s nothing, really.”

It occurred to him, all of a sudden, that he could probably resolve this mess simply by taking the handlink and going back into the Imaging Chamber and encouraging Sam to do something. Anything. Lord only knew what small things would change the future. A dead butterfly in the Cretaceous could lead to a new world government; doubtless Sam Beckett’s choice of breakfast beverage could get Al Calavicci out of an unexpected marriage. . . .

Janna smiled at him.

Well. He didn’t have to change things right away, did he? It could always wait until morning. Couldn’t it? ...

QUANTUM LEAP

OUT OF TIME. OUT OF BODY. OUT OF CONTROL.

To the memory of Dennis Wolfberg, a fine actor who will be sincerely missed by all the fans of Quantum Leap

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks for this one go to the ever-merciful and understanding editors, Ginjer Buchanan and Nancy Cushing-Jones, and to Kathy Mclaren, Anne Wasserman, Kim Round, Lisa Winters (woof woof) and Arianwen, Nancy Holder, John Donne, all those who hang out in Those Topics on GEnie, and all the people I meant to acknowledge all along.

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

PROLOGUE

Somewhere in time . . .

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;. . . any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind . . .

—John Donne, Devotions XVII

Wind in his face. Sunlight.

He wobbled, clenched a rope under his hand and caught himself. Nylon fibers bit into his palm. Ignoring them, he looked around and laughed, delighted. He was standing in the air.

Well, almost—Al was standing in the air; Sam Beckett was balanced precariously on the rounded wicker edge of a hot air balloon gondola, shivering in a cold thin breeze, as close to floating as he had ever been. He could remember being afraid of heights as if the fear mattered to someone else, but up here, up in the perfect silence of the upper sky, the ground had nothing to do with him. He could look down and see carefully groomed fields, Impressionist trees, mitelike cars crawling along lines of highway, and none of it had to do with Sam Beckett. He was the center of a painting, a panorama. Below him was the earth; around him, the sky.

A raven floated by, teetering on the wind, and looked him over with bright black eyes. He reached out with his free hand. The bird squawked indignantly and tilted away to glide on a convenient thermal at a safer distance.

“Er, Sam, don’t do that,” Al advised him. The Observer was concentrating on the handlink, punching a series of patterns on the colored cubes, frowning with pursed lips, trying another series. The wind failed to ruffle his hair, to flutter his rich dark forest green suit with the matching dark green-and-gold brocade vest.

Sam glanced at the man standing on nothing and laughed again. “It’s like flying!” he cried. He didn’t even bother to look to check who he was or what he was wearing this time; he was having too much fun simply looking around at the world.

Behind him, someone else in the gondola laughed in agreement. Sam twisted around to see who shared his delight. A woman in her late twenties, clinging to the opposite side of the wickerwork basket that held them both, smiled widely at him. Sam grinned back.

“Yeah,” Al grunted, not looking up. “Hmmm. Sam, clip that thing there.”

“What thing?” If Al was in a Mood, Sam was willing to humor him. He made a mental note to go hot-air ballooning again, and hoped that he’d remember.

“What?” the woman echoed. Sam could see his own exhilaration reflected in her eyes as she reached for a lever. “Are you ready?” she said.

“That thing there.” Still not looking up, Al pointed with his ever-present cigar to a large metal clip hanging over the edge of the basket.

“Okay, fine.” Sam grabbed the clip, snapped it onto a strap hanging over the nearest piece of gondola, and looked up just as the blower roared to life. The sound was earsplitting; heat slapped at his face and hands. Tongues of fire, nearly colorless against the sky, shot straight up into the mouth of the balloon. Leaning his head back and squinting against the temperature-distortion of the atmosphere, he could see rippling silk panels in jewel tones of red and green meeting in a small open circle, high overhead.

But it was nothing, nothing to the expanse of horizon all around him. The blower shut down, and the balloon floated silent again, serene among the white mountains of the air. He reached out, only half believing the cold wetness in his palm. “I touched it,” he exulted. “I touched the clouds!”

"Ahuh,” Al said, still busily jabbing. He spared a glance to the cloud, which was drifting through his left shoe, and shook his foot automatically to free it. The raven circled him, squawked once, and flapped away. “Nyyyaaahhhh,” the hologram jeered after it.

He could see the curvature of the earth, Sam thought, if he tried. He could calculate how high he had to be to really see it, but he didn’t want to waste the moment with mere calculation. He wanted to step off the wickerwork and spread his arms and follow the raven.

As if in answer to his wish, the woman behind him said, You’re sure you’re ready?”

He answered, “Yes!”

And a solid shove in the small of his back sent him off the edge of the gondola and spiraling down—down, down to the manicured fields, the tiny matchbox cars rapidly becoming larger, and the glory of standing in the sky was abruptly replaced by sheer helpless terror. He slapped at himself desperately, looking for a parachute that wasn’t there, and tried unsuccessfully to kick. He couldn’t. The earth spun beneath him, the tiny images growing, expanding, as if the planet were stretching its maw wide to swallow him.

As he screamed Al descended beside him, ruffled not me whit by the fall, still concentrating on the handlink. Sam retained enough presence of mind to duck his chin in toward his chest, getting his mouth out of the windstream, and yell, “Al! Do something!”

Al looked up, took the cigar out of his mouth, and asked reasonably, “What?”

Sam looked down at the whirling earth and screamed again. The wind of his fall dragged at his face, his clothing, whistled in his ears. Hair whipped into his eyes as the earth rushed up to meet him. It wasn’t fair, he thought, it wasn’t right, he couldn’t die this way, not now, not with his Observer right there and apparently unperturbed; he’d gone too far, done too many things, he wanted to go home, and he hit the end of the bungee cord with a terrific jolt and jerked back upward with Al still beside him, not a lock of hair out of plac

e, and hit the top of the arc to see the balloon with the pilot waving enthusiastically, and fell again, and hit the end of the cord and swung upward, with Al, still beside him all the way, griping, “I wish to heck you’d Leap, Sam. I haven’t been this dizzy since I took zero-gravity in astronaut training,” and above them the woman in the balloon looked over the edge of the gondola, cheering, and all Sam could say as he ricocheted through the clouds was “Oh boy.. . OY...oy...OY...oy..."

And mercifully, Leaped.

FRIDAY

June 6, 1975

Thou art slave to fate, chance. . . .

—John Donne, Holy Sonnets IX

CHAPTER ONE

He was still dizzy, and carrying a weight on one shoulder, and it was dark, and the footing was wet and slippery, as if it had recently rained. It wasn’t surprising that he stumbled.

This time, he couldn’t even remember being in that other place, waiting for an identity, a Voice. This time he had fallen directly into his next Leap. Fallen ... He caught his breath and a nearby tree trunk and shook for a few minutes, fighting residual panic, grateful for the weight he carried if only because it pressed him firmly against the solid ground.

Maybe whoever was in charge of his ricocheting through Time—God or Fate or Chance, Time or Whatever—thought that bungee jumping from a 'not air balloon was just one of those interesting things he should be made to do occasionally for his own good. The fact that he was still shuddering inside from the terror of free fall was irrelevant. He glared up at the sky. “Thanks a lot."

“Hey, you haven’t earned your tip yet,” a slurry voice said from ahead of him and slightly to his right. “Let’s get that 1’il keg over here before you drop it, okay?”

Sam took two more steps forward and found himself in a wide clearing lit by a pair of roaring campfires. Some thirty young people were sitting or standing around, perhaps half of them looking at him expectantly. He could smell cooking meat and burning vegetation and water and pine trees.

By this time he was used to doing a rapid, almost unconscious assessment of Who Am I Where Am I What Am I. He gathered data without even being aware of the process: jeans/heavy laced boots/flannel shirt/“keg” = probably male, probably young; details like personal appearance he could check out later on. Luckily it wasn’t a full-sized keg. Quarter, he estimated. A baby keg. But damned heavy, nonetheless.

The others gathered by the fires, standing or sitting on deck chairs or blankets to protect themselves from the muddy ground, were all about the same age, in their late teens. They all wore slacks cut suspiciously full from the knee down, and variations on T-shirts and long crocheted vests. He automatically noted the fashions, wishing he were a computer using parallel processing so he could check them against a mental database while simultaneously keeping on his feet. At least the vertigo from the balloon jump was fading.

There was a definite nip in the air. Sam could feel himself drawn to the warmth of the fire, bright flames against the darkness, smaller cousin of the flames that provided enough hot air to keep a balloon sailing proudly through the clouds.

“Hey, bo, put it over there,” a young male voice instructed him. Still disoriented from the bungee jump, Sam carried the keg over to a rack set up between the two campfires and set it down, rubbing his shoulder. He didn’t care what condition this body was in, putting the cask down was a relief. It must hold seven or eight gallons of beer. He wondered whether these kids were planning to drink it all.

The owner of the voice, a boy/man sporting bushy light brown sidebums and a sneer, was waiting when he turned around, fingering bills out of a wallet. “Four bucks, right, with the delivery?” he said.

“Yeah, that sounds about right.” Sam had no clue whether it was right or not. From the look in the kid’s eye and the snigger he cast over his shoulder, Sam was being shortchanged. Well, it wasn’t his fault he didn’t know the going price in these parts. He hadn’t figured out where these parts were yet. Or when, for that matter.

He was up in the mountains, though, he could tell that much. The air was thinner, and the pine looked right. Not western mountains; somewhere back east, he thought, judging from the undergrowth he’d slogged through to get to the party. He’d have to find a newspaper, or a phone book, or a map. Preferably a newspaper, so he could pin down the date, too.

Meanwhile he took the proffered money and wondered what he was supposed to do next. Go back the way he came, presumably. He started off in that direction, hoping desperately for a clue to his location, his identity, what he was supposed to be doing, anything.

One of the kids staggered as he passed, almost fell into the nearer fire, and he reached out and grabbed without thinking, pulling the boy to safety. Nobody else reacted, except to laugh. He set the kid back on his feet and looked at him more closely, and then around at the others.

They were all drunk, every one of them. Not a little drunk, either. The ones on their feet were barely standing up. The boy he’d pulled out of the fire was swaying, giggling, and Sam caught him again just in time to lower him to the ground before he fell there.

Over at the edge of the clearing, one of the girls turned suddenly and vomited into a bush.

“Oh, boy,” Sam said in utter disgust. And then he looked at the keg again, and realized his own part in the party. Or at least, his host’s part. “Oh, boy.”

He was dizzy, off balance; suddenly he wasn’t carrying the keg any more, and it wasn’t dark. The air didn’t even smell right. A split second later he realized he was flat on his back looking up at a plain white plastic-looking ceiling, and the breeze on his face was artificial, from air conditioning.

He sat up slowly and looked around.

He was in a bed, and all kinds of monitors were stuck to him, with wires leading to a bank of instruments behind him. Over against one wall, some twenty feet away, a set of stairs led up to an observation deck, glassed in. Lights on the machines up there were going crazy, blinking on and off. He wasn’t wearing anything under the covers, as far as he could tell.

He shook his head and squeezed his eyes shut, cautiously opening them again after a count of ten. Nothing had changed.

It must be a hospital of some kind, but how had he gotten here? He didn’t feel sick or hurt, except maybe a sore spot on his arm where an IV tube was taped in place. And the only times he’d ever been to a hospital it was just to the emergency room, and there were doctors running around all over the place, and the place stank of blood and fear and medicine, and there was always lots of shouting and confusion, people sitting in chairs by the walls crying, arguing with nurses at the desk about insurance. It wasn’t like this.

This was quiet, as if somebody’d wrapped cotton wool around his ears, and empty. He was alone except for the machinery with the blinking lights.

Throwing the sheets aside, he swung his legs over the edge of the bed and peeled the sensors off his chest and legs. He was getting the last of them when he happened to look down and really see his torso.

He didn’t remember having that much hair on his chest.

And he knew for certain he wasn’t that pale.

There were a few other things that weren’t quite the way he remembered them, either. He opened his mouth to ask the empty room what the heck was going on when a door just outside his peripheral vision opened, and he looked up to see a tall black woman dressed in a deep red dashiki sweep in. His first instinct was to demand, “Who are you?”

He heard the woman say, “Ziggy! Class three, stat!”

And then something warm hit him in the face and he folded over, not even having time to cover himself back up again, and the white room faded away.

The woman in the red dashiki paused several feet away until another woman’s voice, from out of nowhere, advised, “The atmosphere is clear, Doctor.” The air pressure creating a minor wind at her back—a wind that had kept the gas from her in the first place—abated. She strode over to the recumbent form, sprawled on the floor beside the examination be

d, and sighed. “Well. Do you suppose he’s going to stick around in this one long enough to find out anything about him, Ziggy?” Her antecedents were a little confused; it didn’t bother her. Confusion came with the territory.

“If you’ll be so good as to roll him over so my sensors can scan more efficiently, you can remove the remaining medical monitors,” the disembodied voice said. The words were considerably more polite than the tone was. The woman in red gritted her teeth and did as requested. In the process she was careful to peel back both eyelids, revealing blank hazel-green eyes. A beam of red light made a swift pass before they could roll back up into his head.

“Scanning,” the voice said, suddenly toneless. “EEG readings confirmed. Elimination process proceeding. Positive identification markers noted. Scanning data banks for corroboratory material initiated.”

There was a pause, while the woman in red lifted with practiced skill and got her limp and unresisting patient back into the bed. It would have been nice to have help with this task, but there were security considerations. What happened here, on a regular basis, was known to very few, and she was committed to keeping it that way. She’d removed nearly all the apparatus, including IV tube and catheter, when the disembodied voice spoke again.

“Preliminary cross check through: birth reports, Selective Service records, state licensing agency records. Index check. Processing.”

The woman in red barely heard the words. She straightened the pillow, moved an IV pole back out of the way, and twitched a sheet into position. Then, gazing down on the recumbent body, the familiar face with the single lock of white hair drooping into its eyes, she sighed. “Dear one, when is all this going to quit? Mamma really does want to know.”

The unconscious body didn’t respond.

“I have a tentative ID,” the voice said.

“You better let the Admiral know,” the woman in red answered. She looked back at the body again and moved her head slowly back and forth, her long earrings swaying in glittering constellations against her neck. “Here we go again,” she murmured. “When you coming home, honey? When you gonna come home?”

Quantum Leap - Random Measures

Quantum Leap - Random Measures